Asian American Motherhood Has Always Been Political

From the 1875 law barring Chinese women's entry to facing police brutality, Asian American mothers have always fought to build families in a country that questions their right to belong.

On August 24, 1874, Chy Lung stood on the deck of the steamship Japan, watching San Francisco's harbor come into view. After a long, arduous journey from China, she was ready to disembark and begin her new life. What she couldn't have anticipated was becoming one of twenty-two Chinese women detained the moment they arrived—all labeled "lewd and debauched" without a shred of evidence. Immigration officials presented an impossible ultimatum: pay a $500 bond per woman (an astronomical sum at the time) or face immediate deportation.

Lung had arrived in the United States at the peak of anti-Chinese sentiment when women often bore the brunt of xenophobic policies. Just four years earlier, in 1870, California had passed an immigration statute requiring East Asian women to provide "satisfactory proof" of their "good character" and confirm they were "traveling of their own free will"—scrutiny applied to no other immigrant group. Officials were particularly fixated on preventing sex work, though the broad language gave them near-unlimited power to deny entry.

Unlike many others caught in this web, Chy Lung refused to accept her fate. Her case, Chy Lung v. Freeman, climbed all the way to the Supreme Court—and in a surprising turn, she won.

However, by the time the Court issued its decision, Congress had already passed the Page Act of 1875—one of the first pieces of federal legislation specifically targeting Asian immigrants. While including other provisions, the Act's most aggressively enforced restriction focused on Asian women, forbidding their "importation for purposes of prostitution." Like the California law before it, the Page Act empowered federal immigration officials to make subjective determinations about whether Asian women were being trafficked "for lewd and immoral purposes” and barred from entry.

Here's what we don't talk about nearly enough: one of America's first restrictive federal immigration laws wasn't aimed at criminals or political dissidents. It targeted Asian women's bodies specifically. This wasn't just about controlling the workforce—it was about controlling families, bloodlines, futures. Whose wombs were welcome? Whose motherhood counted? The Nation reports, “For Chinese immigrants in particular, the Page Act meant that we allowed Chinese men to enter, but not women. So that meant they couldn’t form families—you had these bachelor societies. If you don’t let the women enter and form families, you have the bachelor men who are easier and cheaper to employ than a man who supports a family.”

Long before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, before today's heartbreaking family separations at the U.S.-Mexico border, the playbook was already written—control women's entry, and you control a community's future.

The Ripple Effect Through Generations

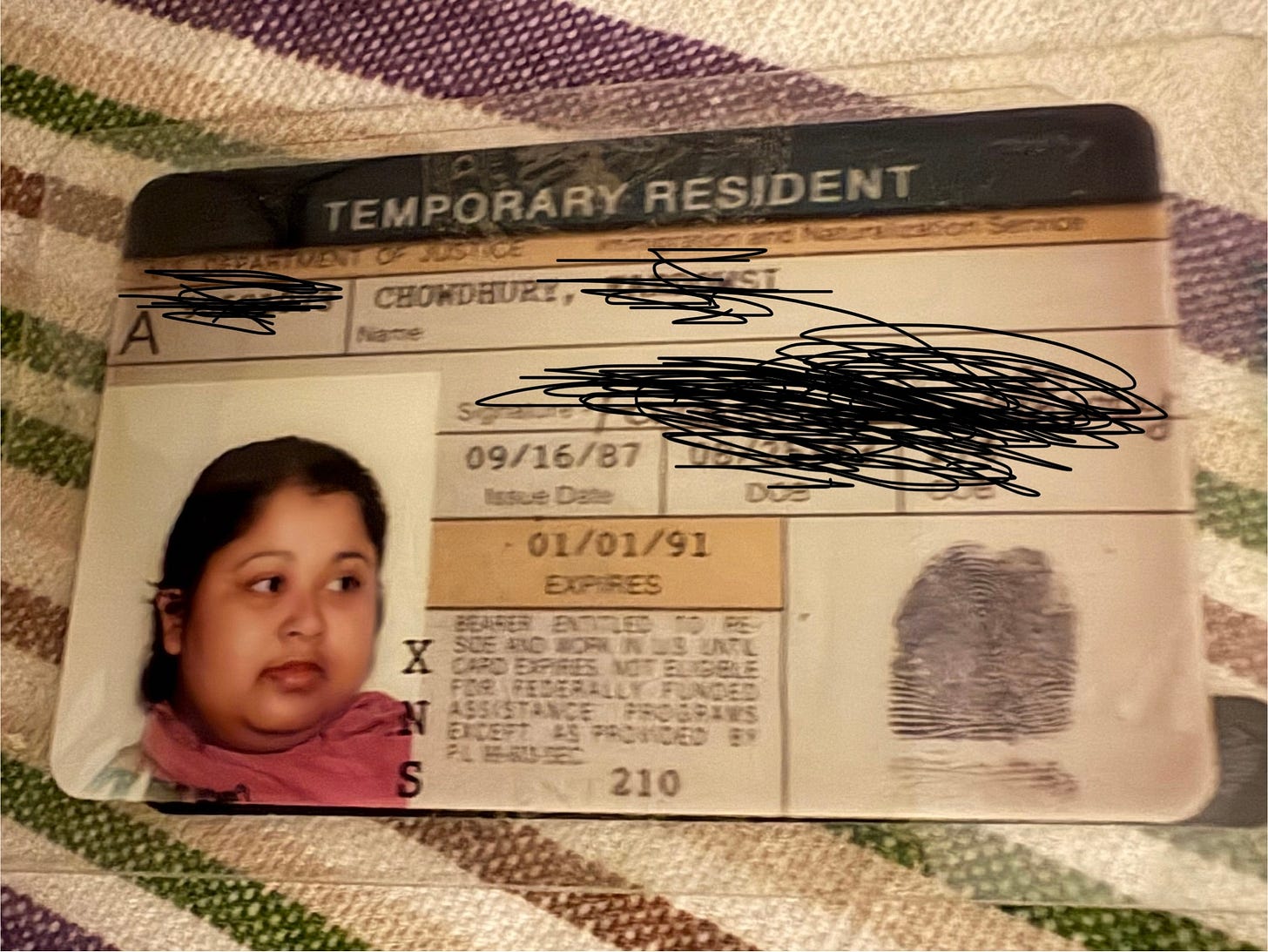

This month, we honor both Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month and Mother’s Day—two observances that sit uneasily together for many immigrant families. Asian American women have long been written out of history’s center and made invisible in the retelling of both Asian America and motherhood itself. This legacy of controlling Asian women's bodies and families continued to ripple forward through American history.

Japanese American women gave birth in prison barracks during WWII internment, their infants registered with numbers instead of names—their motherhood criminalized by the government.

Southeast Asian refugee mothers arrived in the U.S. —haunted by war, genocide, and displacement. They had fled the killing fields of Cambodia, the jungles of Laos, or postwar Vietnam, crossing oceans in makeshift boats, crammed refugee camps, and bureaucratic purgatories only to resettle in neighborhoods hollowed out by disinvestment and redlining.

South Asian and Muslim mothers raised children under post-9/11 surveillance, teaching them to keep their heads down, their names quiet, their bodies small—motherhood as protection through invisibility.

Today, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander mothers continue facing some of the highest maternal mortality rates (nearly five times higher than white people) in the U.S., battling systemic healthcare neglect—motherhood as a life-threatening endeavor.

And yet, through every policy designed to exclude, surveil, control, or silence, Asian American mothers kept building families. They birthed children into a country that questioned their very right to exist here. They passed down languages, recipes, lullabies, prayers, and sometimes necessary silences.

A Mother's Cry: From Historical Pattern to Present Reality

On March 27, 2024, Noton Eva Costa, a Bangladeshi-American woman stood in her Queens, New York kitchen, desperately shielding her son, nineteen-year-old Win Rozario, who was experiencing a mental health crisis. He had called 911 himself seeking help. But when NYPD officers arrived, their weapons were drawn.

Please! Please don't shoot!" Noton begged, arms outstretched to shield her son.

"Please don't shoot my mom!" Win's younger brother cried out.

Body cameras captured their pleas. But moments later, officers fired tasers—then guns. Win died in front of his mother, in their home, after calling for help.

Noton's cry joins a long, heartbreaking chorus of immigrant mothers who've tried to stand between their children and systems that see them first as threats. Her story connects to Black, brown, Asian, and Indigenous mothers who've positioned their bodies as human shields. Her grief reminds us that even now, in 2025, motherhood for many Asian American women remains an act of defense—a daily calculation of survival.

The Bridge Generation

Many of us in the AAPI community are raising our kids while caring for aging parents—becoming human bridges between generations, between cultures. Like so many immigrant daughters, we translate in both directions. We become the interpreters, the form-fillers, the appointment-makers, the cultural navigators. We explain medical jargon to our parents and cultural nuances to our children. We step into silences no one else will fill.

We raise our children with a complicated knowledge: they are deeply loved and constantly at risk. We know the world will see them first and sometimes only as brown bodies, as descendants of immigrants.

We want desperately to give them freedoms our mothers couldn't give us. We want them to carry lighter burdens. But we can't pretend the world away. We can't unwrite the systems they're growing up in.

This is why we must document these stories.

I write about migration not as a single border crossing, but as a generational state of being. I write about motherhood not as sentimentality, but as a political act. I write about belonging as something we keep chasing, knowing it's designed to stay just out of reach.

In a time when diversity initiatives are being dismantled, when Asian American and Pacific Islander histories are being erased from classrooms, when immigrant communities are scapegoated again, the stories of Asian American motherhood deserve to be told. These stories are our collective history—the untaught lessons of how Asian women have been building America's future, generation by generation, against all odds.

We come from women who survived. We are the children of women who endured. And we mother on—differently, defiantly, deliberately.

Happy Mother’s Day.

Thank you so much for writing this! I was particularly struck by the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander maternal mortality data. It is horrifying to see that becoming a mother can pose such a high risk for women. Really appreciate you shining a light on the issue.