Astoria to City Hall: The Grassroots Power Behind Zohran Mamdani’s Win

A love letter to our new mayor and to our beloved NYC.

The night New York City elected its first Muslim South Asian millennial mayor, I took my five-year-old daughter to an election party in Astoria—the neighborhood where I was born, where my children were born, and where Zohran Mamdani first cut his teeth in politics.

I wanted her to remember that this happened in her lifetime, that she was part of the generation after her mother’s, who grew up in fear, under the shadow of 9/11. For Muslim families like ours, who’ve called Queens home for decades, the moment carried a weight that can’t be measured only in votes.

Astoria’s streets hold so many of our stories—the immigrant dreams, the surveillance years, the slow rebuilding of community trust. As a journalist who has spent years documenting Muslim life in America, I’ve watched how our neighborhoods have been both targets of suspicion and sources of resilience.

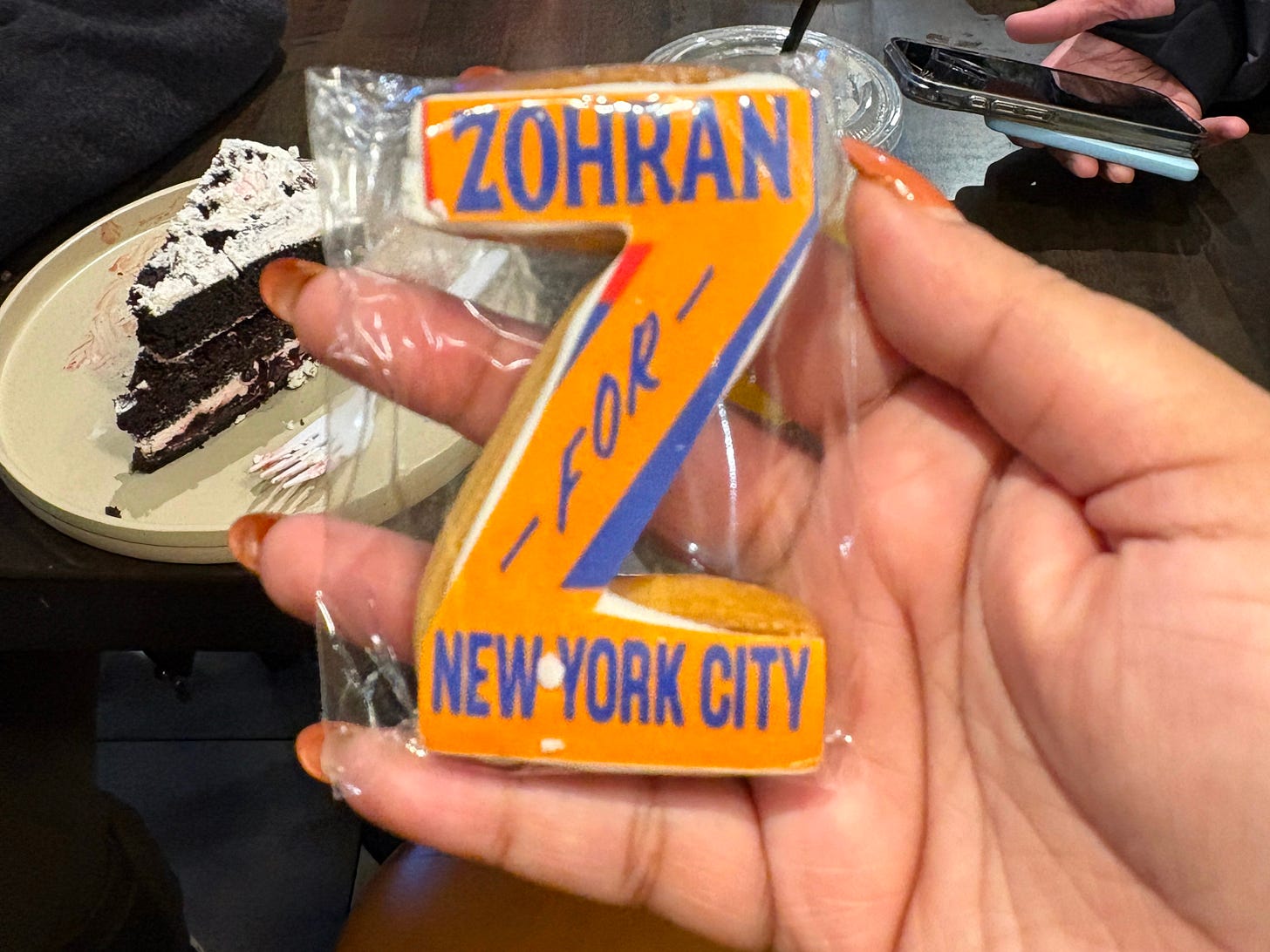

When I reported for Harper’s Bazaar this summer, I followed the grassroots organizing that made this victory possible—the years of tenant meetings, street canvassing, and the immigrant aunties everyone dismissed until Mamdani himself shouted them out in his victory speech. His rise didn’t come from political machinery—it came from those who, for years, knocked on doors no one else bothered to.

And as Moustafa Bayoumi reported for The Guardian, Muslim New Yorkers—now numbering nearly a million—have become a political force no candidate can afford to ignore. For decades, our communities were either surveilled or sidelined. Now, they’re shaping the direction of the country’s largest city.

That power comes with the weight of memory, though. In The New Yorker, Rozina Ali described how Mamdani finally decided to address Islamophobia directly near the end of his campaign—standing before a Bronx mosque and speaking tearfully about what it means to be Muslim in New York after 9/11. He recalled being interrogated at an airport, asked if he had plans to attack the city; an aunt fearful of wearing her hijab; a classmate pressured to become an informant. “To be Muslim in New York is to expect indignity,” he said. “But indignity does not make us distinct—there are many New Yorkers who face it. It is the tolerance of that indignity.”

Those words landed deeply. I remember the early 2000s, when my Bangladeshi Muslim boyfriend, then a flight student, faced relentless racial profiling. We lived through the fear that any conversation could be misinterpreted, any mosque could be monitored, any young man could be entrapped.

As I reported for New Lines magazine, for years, entrapment cases targeted young Muslim men, including those with mental illness or developmental disabilities. Law enforcement supplied fake weapons or goaded them into extremist rhetoric—“preemptively” arresting them for crimes they were coaxed into. NYPD informants embedded in the Bangladeshi-American community later described how they were told to “create and capture” conversations about jihad or terrorism. Fear became the price of being visible.

Two decades later, to see a Muslim mayor in City Hall is to witness a collective exhale. But it’s also a reminder that visibility doesn’t erase the past —it transforms it.

When I looked down at my daughter that night, I thought of my parents, who came to this city believing hard work would earn them belonging. I thought of my generation, who grew up understanding how fragile that belonging could be. And I thought of hers—the one that might finally see being Muslim in America as something ordinary, not political.

This morning, while brushing our teeth, I confirmed to her, “We have our first Muslim mayor.”

She looked up at me and asked, “like me?”

“Yes, Mama,” I said. “just like you.”