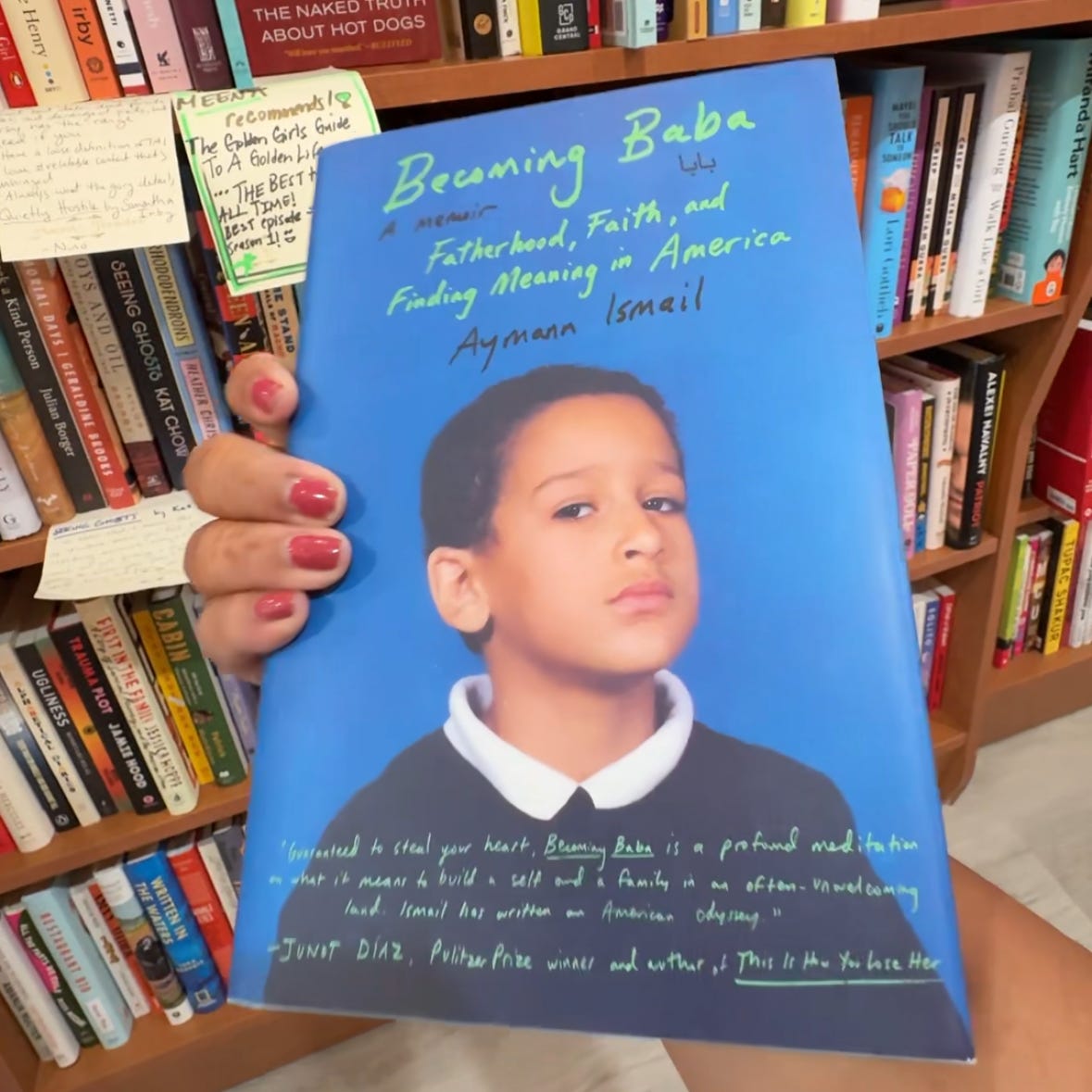

Diaspora Dialogue: Aymann Ismail is Redefining the Muslim Memoir

In Becoming Baba, a journalist and author tears up the post-9/11 script for Muslim storytelling.

For decades, Muslim American stories have followed a familiar script: explain, defend, humanize, repeat. In the long shadow of 9/11, Muslim writers have been expected to soothe Islamophobia rather than tell the truth of their lives. Aymann Ismail, a journalist and son of Egyptian immigrants, tears up that script in his debut memoir, Becoming Baba.

His coming-of-age story moves from gender-segregated Islamic school classrooms in New Jersey to getting high and praying with his wife after their second child is born—embracing the contradictions many Muslim writers have been afraid to voice publicly.

In our conversation, Ismail was as candid as his prose, bracing for the criticism he knows is coming both from within his own community and the usual suspects outside of it.

I read your book in a day and a half, which, as a parent, is saying something. What I loved most was how messy it is, how you don’t try to tie everything together neatly. Throughout all these different chapters of your life, there’s this central question: what kind of Muslim am I supposed to be?

Aymann Ismail: You’re on the money. When I first sat down to write the book proposal, my first draft was all about the trauma—here’s why I blame the world for who I am. When I read it back, I felt disgusted with how little I appreciated the experience. I started thinking about who was telling our stories as a community and what they were prioritizing.

As Muslims, we spend so much time trying to explain our humanity that we’re stuck having the same conversation over and over. What people were saying in defense of ourselves after 9/11 are the same things you’ll hear someone say 25 years later. We’re constantly trying to meet people where they are rather than being honest about what we’re actually experiencing.

But, I thought what’s more valuable than rehashing trauma? Celebrating the love stories. Understanding your parents better than you could when you were younger. Finding the joy. The way I approached the book totally changed—it wasn’t about the biggest factors in how I thought about Islam or identity. It was about these unbelievable stories, these strange vignettes in the life of an ordinary kid who just wants to do better because his parents set the bar somewhere, and he wants to reach it.

Let’s talk about Islamic school, which you first went to and then transferred to public school later on. There’s a moment in the book where your friend says, “Everybody who goes to Islamic school comes out so messed up.”

It’s not one-size-fits-all—it depends on your lifestyle at home and what your parents’ tolerance is for reinforcing those values. In my case, it was extremely enforced. One day, you’re in a class full of boys and girls, and the next day, you’re in third grade, and you’re separated. The idea is you’re very different from each other, you have different needs and talents, and that’s it.

For me, that was the first crack in my faith journey because I knew it was bullshit. You don’t have to be older to know this doesn’t make sense—that they’re projecting these false ideas where if you put two third graders in a room, they’ll end up having sex. It was the first time I doubted that Islam made sense to me. It almost felt like this was just a way to tell us what to do all the time.

You spend five or six years totally separated from girls, so you lose the ability to talk to them and see them as just like you. I needed to relearn that later in life.

But you’re considering Islamic school for your own kids?

I want to put them in an Islamic school, and the reason I’m not so afraid of the gender stuff is that if you’re at home giving them opportunities to interact with girls in a way that they see the humanity in each other, that could make a world of difference.

Then you get to college and try to join the Muslim Students Association.

I was excited about making new Muslim friends. In public school, I was the only Muslim kid—everybody expected me to explain everything about Islam. I missed just being one of many Aymanns. But what I got at MSA was really different. It almost felt like everybody in charge was a proxy for my parents.

They wanted to gender segregate the spaces so women were sitting in the back and men in the front. We weren’t praying—we were just talking, organizing, wanting to have events. All you’re saying is you’re relegated to the back of the room because of who you are, and there’s no choice. I didn’t agree with that.

I felt like I’d seen too much of the world to ever go back and live that kind of life. But then I started making Muslim friends outside of MSA who shared the same frustrations. One friend, Haniya, was a Muslim girl who wanted to find a husband so she could get out of her parents’ house. I couldn’t believe it—you’re so young, we’re still kids. That really helped me understand that my slice of Islam was small.

I found your friend Haniya’s storyline interesting in contrast to yours. You guys meet in college and she’s super concentrated on finding a husband in between studies, while you’re just trying to figure out life. I appreciated seeing her story from the perspective of a Muslim male writer.

Male writers often write women who just exist for something to happen to them. I did a pass after the first draft to make sure all the women in the book didn’t just exist for something to happen and then move on. I wanted to make sure she came back.

My sister also comes up a lot. For a book about masculinity, there are more female characters than male—there’s only one consistent male friend. All the women taught me how to be a man.

Let’s talk about meeting Mira, your wife. You come from very different backgrounds, even though to the outside world you’re both Muslim.

When I met Mira, she encouraged me to go and find answers for myself for the first time. That goes against everything I learned about how to be a Muslim. My mom would say: there are scholars who do this, neither of us have the expertise to interpret this stuff, we have to rely on the scholars, don’t inflate yourself.

What makes Mira different is her whole interpretation—going back to her family, how she grew up with Islam in Kentucky—really came down to one’s personal relationship to their faith. All of her siblings pray religiously. They’re the kind to sit around in the evening and just open the Quran and read it for fun. I’ve never seen that in my generation of Islamic school kids.

I didn’t grow up with that curiosity. I grew up with the intent to follow rules because they were already packaged and delivered to us—they wanted us so badly to be good Muslims that they invested everything in muscle memory.

There’s a powerful passage where you struggle with the Quranic verse that is commonly interpreted as men being allowed to hit their wives and Mira helps you think about it differently.

I came across that verse and had a crisis. I was like, this doesn’t make sense—why would God want you to be merciful and loving, but then if your wife disagrees with you, one of the steps is to hit her? If I hit my wife, she’ll beat my ass.

Mira challenged me. Are you going to assume that because it’s in the Quran there’s only one way to interpret everything? If God is infinite and Islam is for all people of all time, wouldn’t it make more sense if there were infinite ways to interpret everything?

She asked me to think about how the word “daraba” appears in other verses. In another context, it’s translated as “to run away,” “to hit the ground running.” She gave me the example of hijab—how it’s used several times in the Quran, and in one verse it’s a literal sheet separating rooms to give women privacy.

Even in the process of having those conversations, I felt closer to Islam than any time I got up and prayed.

You write that after meeting Mira, you “actually became Muslim for the first time.” That’s a bold statement.

Her understanding is that it’s all about being a seeker yourself and finding the knowledge. It’s not that you’re going to find the answers right away—the process of going and looking for answers is what makes you a Muslim. If we’re going to be judged for our understanding and there’s no pope, no imam giving you permission to go into heaven, you’re going to be there alone with God. It would make sense that your life should be dedicated to forging that connection.

Let’s talk about raising kids in Newark, where you grew up. When you found out you were having a child, you questioned whether to stay.

It really feels like everything is at stake, like every little move will alter their chances at succeeding. I know we’re self-inflating our worth as parents, but when you first become a parent, you feel like one move could be the difference between a full ride to Harvard or community college.

Living in Newark, where the pollution is so bad we have the highest rates of asthma in the world, people come from Finland in hazmat suits to collect our soil. There’s so many times—you remember we used to have a pool here, then it shut down because they found crazy toxins. They used to manufacture Agent Orange there.

The question is: do I stay and roll the dice again? Do my kids deserve better?

But you stayed. In fact, you make the argument that “the suburbs are haram.”

I feel like the suburbs create a hierarchy based on how far you can travel and the size of your house. Whereas in the city, even if you have a lot of money or you don’t, you’re all going to the same place. We’re all going to meet up where our friend got the new video game.

People in the suburbs want to collect everything—the biggest TVs, a bowling alley, a pool—rather than just going to those places. In the city, I don’t buy more than one loaf of bread at a time because I can walk three doors down and grab it from the bodega.

When you go up to pray, to your left is the janitor and to your right is the CEO. The person doing the call to prayer has been Muslim for six months and the imam has been Muslim his whole life—it doesn’t matter. We’re all just going to the same place to do the same thing. That’s why I feel like the suburbs are haram.

There’s a scene near the end where you and Mira get high after her breastmilk dries up, and you pray together. That’s already stirred up some controversy among your Muslim readers.

When my wife’s milk dried up, I realized this means she has her body back. We used to get high together before we became parents. It felt like the perfect way to reconnect.

She prays because she’s a real Muslim, and she invited me to pray even though we were still high. In the back of my mind I’m thinking, in the Quran it explicitly says you need to come to prayer with a clear mind. But I see the person who’s actually religious, who doesn’t miss a prayer, who really loves Islam, not be so concerned by it. That gave me the bravery.

Then our kid joins us to pray for the first time. As any Muslim parent will tell you, it’s a big feeling. No matter how much I complain about my mom thinking passing down Islam is tied to her success as a parent, it’s intrinsically true of me, too. That’s a moment where I’m becoming my parents.

I know this is a line for some Muslims. What I don’t want you to think is that I think it’s okay. I just want you to give me the space to tell my story as I experienced it.

You also write about returning to Egypt as a journalist and getting attacked by a mob.

I got beat up. I got headbutted in the face by a grown man who took my camera—a brand new full-frame 6D with a 24-70 Canon L series lens. It was all of my money. When somebody took it, I was not about to just let it go. So I chased after him.

But I wouldn’t want my kids in that situation. I do want them to go back to their homeland. That’s the primary reason I’m putting them in Islamic school—so they can learn Arabic and communicate with their family back home. That fear of them being tourists in Egypt terrifies me.

Your book comes at a time when the stakes feel incredibly high for Muslim representation. You must have anticipated backlash.

The stakes are so high through no fault of our own—we’re in this position where we need to be perfect all the time.

Of all the suffering Palestinians have been through, there are still people falling in love, grandparents hugging their grandkids. There’s love. It’s really worth it for us as young families to not forget we have a responsibility to ourselves to not be in defense mode forever.

Final question: What do you want readers to take away from this book?

Be open-minded, be generous. Give me an opportunity to tell my story the way that I remember it, the way I feel it’s valuable. You’re not going to agree with everything. This is not a book where the Muslim character is always doing the Muslim thing.

But I feel like it’s valuable because it’s part of our story, part of our heritage. It’s one of the first chapters in this next iteration of what Islam is becoming in America. What I want is for people to read it and get a sense for their place in the broader American Muslim story. It’s a history that deserves its own narrators.

And we’re doing the thing our parents couldn’t do—being human for our kids.

This looks right up my alley! Will add to my to-read list. I feel I was raised similarly, where I was shown Islam as a checklist of things to do. As I’m older now, while I appreciate knowing how to read Arabic and pray, I wish there was more questioning and safe space where I was allowed to openly think. Thanks for this interview. How did you come across this author and his book?

Ismail's willingness to show contradiction without apology feels overdue. The passage about Mira challenging his interpetation of that Quranic verse was particularly compelling, especially the conversation around daraba and how meaning shifts across diferent contexts.