ESSAY: All eyes on Muslims in America

For decades, Muslims in America have lived under surveilance. They've gone from fearing it to challenging it.

In 2004, I was dating a boy from Brooklyn training to become a commercial pilot. It was a sweet story—two first-generation Muslim Bangladeshi-American kids in their early twenties building careers in journalism and aviation.

But attempting to get a pilot’s license with brown skin and a Muslim last name just a few years after the 9/11 attacks was actually a terrifying ordeal. By the time, I met T., he was halfway through the various flight certifications, tests and hundreds of hours of flying time needed to become a pilot—and worried constantly that he’d made an impossible career choice.

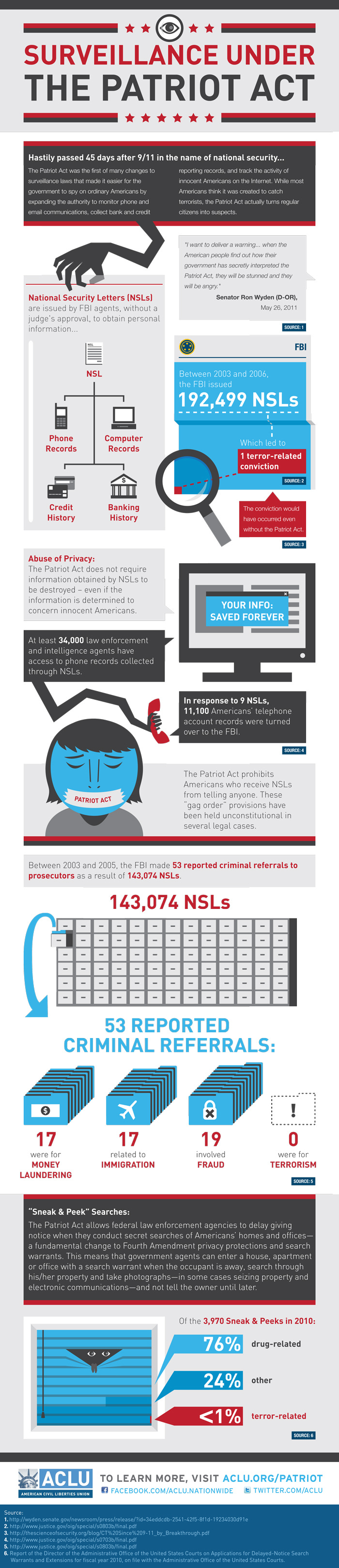

After 9/11, the U.S. government passed a series of surveillance and anti-terrorism laws at record speed. The most recognized one is the Patriot Act, passed just 45 days after 9/11. It expanded law enforcement’s ability to access people’s phone records, bank records, Internet activity and other personal information “in the name of counterterrorism and national security”, according to the ACLU. The Patriot Act made it easy to spy on ordinary Americans, but it was Muslim and Arab communities that the government was actively tracking.

As a pilot-in-training,

the FBI made a few appearances in T.’s life. They contacted his ex-girlfriend in Atlanta to ask invasive questions to confirm whether they were together at certain times, on certain days, or eating in certain restaurants during their courtship. Even after he finally got his first job as a pilot and we went on vacation to the Bahamas together, I sensed his nervousness while passing through security.

Thinking back to two decades ago years ago, I realize now neither of us were particularly attached to our Muslim identities—religion was a bit of background noise at that point of our lives. We identified more closely with our South Asian identities, surrounded by friends who were immigrants or children of immigrants from all over the Indian subcontinent.

But stories of friends, neighbors and family members facing deportation or making the choice to leave the United States before they were forced out became a startling reality due to the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS), commonly referred to as Special Registration. In 2002, Special Registration required all males from a specified list of Arab and Muslim countries to register and submit their fingerprints to the government. According to a 2004 report by the American Immigration Council, the people most affected by Special Registration have been non-Arab Muslims, in particular Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.

As a non-Arab Muslim, I had very little awareness of the long history of surveillance against Arabs in America, even before 9/11. Professor Moustafa Bayoum writes in the Guardian that the anti-Muslim focus of the “war on terror” policies “was built on a pre-existing foundation of hostility to the Palestinian liberation movement”.

According to Bayoum, shortly after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, Arabs and Arab Americans organizing for Palestine became subject to warrantless government surveillance. In 1972, the Nixon administration began “Operation Boulder” which screened the visa status of applicants with Arabic surnames. After September 11, existing programs that targeted Palestinians and Arabs were reimagined for Muslims in the United States.

As I previously reported for Prism, the aftermath of October 7th and the devastation of Israeli air strikes on Gaza has divided the American public and unleashed a new wave of Islamophobic sentiment in the U.S. According to a Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) report earlier this year, the number of anti-Muslim complaints filed with the organization in 2023 increased 56% from 2022.

“The powers that be still expected us to be the same community we were right after 9/11, to put our heads down and try to blend in and not make waves,” Eman Abdelhadi, activist and assistant professor at the University of Chicago whose work focuses on Muslim-American communities said to me in an interview. “We have to demand power and that's what we've been doing.”

Despite the fact that Muslim Americans hail from every corner of the globe,the diaspora has been coalesced into one for the convenience of those doing the surveillance and by our own choosing, for the convenience of surviving and advocating. Whether it’s fighting back against Trump’s Muslim ban or mobilizing to demand a ceasefire before committing votes in the upcoming U.S. Presidential elections, the larger Muslim community is putting cultural differences aside to use our collective civic power.

Read more from the Muslim diaspora:

American Muslims are in a painful, familiar place by Rozina Ali for The New York Times

How U.S. Muslims have transformed in the 20 years since 9/11 and what it means in the wake of 10/7 by Eman Abdelhadi for In These Times

The decades since 9/11 prepared Muslims like me for 2023’s Islamophobic spike by Fareeha Rehman for MSNBC

How Muslim-American communities are rewriting the narrative of American belonging beyond the War on Terror by Anna Beahm for Reckon News