ESSAY: Bad Bunny’s Upcoming Super Bowl Performance Reminds America That Language Is Power

Language is inheritance — and sometimes, rebellion.

Growing up bilingual can be both a flex and a burden. Twenty-two percent of Americans over age five speak a language other than English at home—so for many of us, English becomes a quiet test of belonging. How many times have we heard, “Your English is so good,” and had to smile and say, “Yeah… because I was born or raised here?”

This week, I’m writing about that in-between space — what it means to speak the colonizer’s tongue fluently, and the complicated feelings around passing (or not passing) our mother tongue to our kids.

If this piece resonates, please like, share, or consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support keeps Port of Entry going—and keeps diaspora storytelling alive because mainstream legacy refuses to acknowledge our stories.

With love and gratitude,

Jennifer

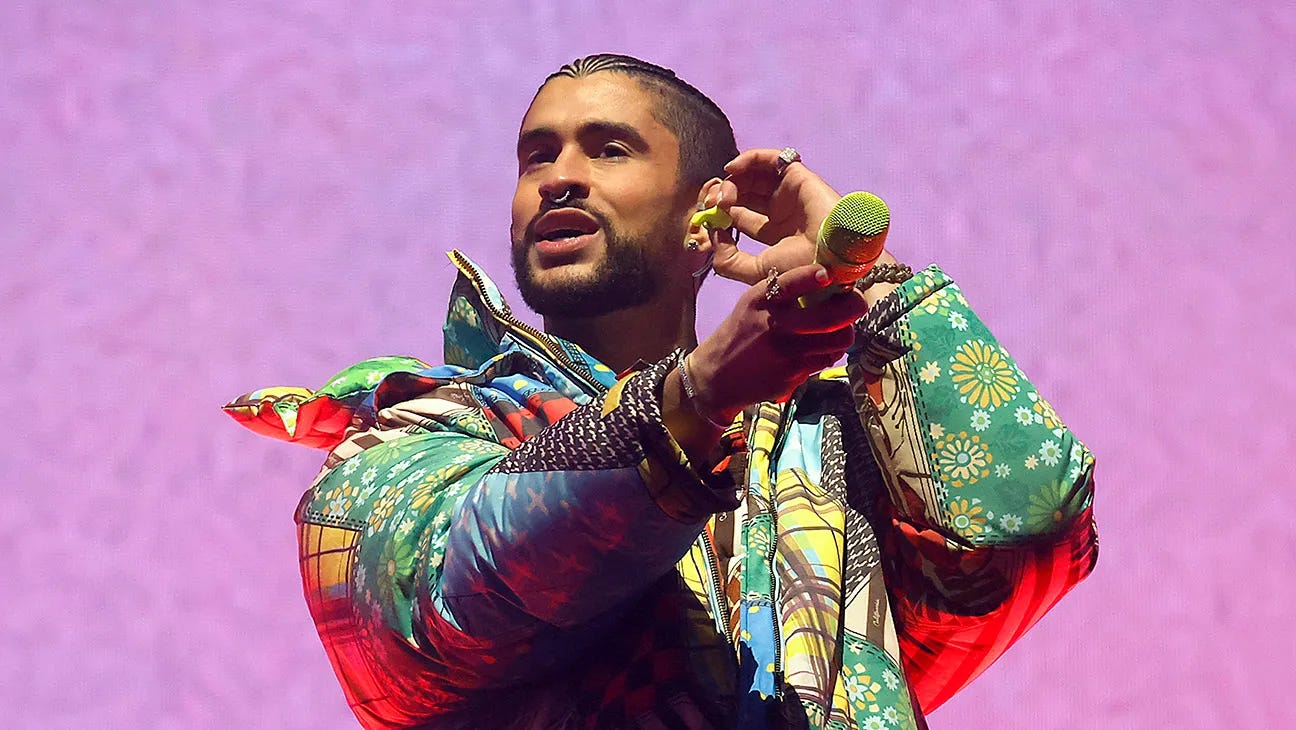

As award-winning Puerto Rican singer, rapper and songwriter Bad Bunny prepares to headline the 2026 Super Bowl halftime show, he’s already sparking controversy—because he sings in Spanish. The Puerto Rican superstar refuses to perform in English publicly, despite being fluent, making a deliberate political statement about language, culture, and belonging. Politicians like Marjorie Taylor Greene have reacted by calling for English to become the official language of the United States, a symbolic and punitive gesture aimed at silencing Brown communities.

This debate is not new. English is the most widely spoken language in the U.S., but it’s far from the only one. According to the 2025 U.S. Census Bureau, approximately one in five Americans speak a language other than English at home—with Spanish leading the pack, with over forty-two million speakers. Spanish, after all, has deep roots in this country, predating English in much of what is now the Southwest.

In fact, the Spanish were the first Europeans to colonize parts of what is now the United States. St. Augustine, Florida, was founded in 1565—the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the continental U.S.—decades before the English arrived at Jamestown in 1607. Spanish missionaries and settlers spread their language and culture across Florida, New Mexico, Texas, and California. French colonies soon followed in Canada and along the Mississippi River. English became dominant not because it was “first,” but because of power, war, and imperial expansion. After defeating the Spanish Armada in 1588, Britain emerged as the dominant colonial empire. English-speaking colonies grew along the Atlantic coast, and after the American Revolution, the United States inherited English as its de facto language, reinforced over centuries through schools, laws, and immigration policies.

In the Southwest, in the Caribbean diaspora, and across immigrant communities, Spanish has persisted for centuries through families, migration, and resistance. Still, it is often treated as “foreign,” reflecting anxiety over identity and belonging rather than any threat inherent in the language itself.

In my own life, Bangla played a similar role—alive in my home, shaping identity and connection, even as the world around me treated English as the measure of belonging. Bangla survived in my own household, quietly resisting erasure. But even when a language has deep roots, the systems around us often insist on measuring belonging by English fluency.

When I started kindergarten, I was placed in an ESL (English as a Second Language) class. Strange, because I was born and raised in the United States—and I could already read and write in English before setting foot in school. My Bangladeshi mother, who had homeschooled me, taught me numbers, letters, and even basic math. We didn’t have preschool. What I did have was a stay-at-home mother who determined that I could speak Bangla and English as well as the other.

At home, English wasn’t allowed. My mother wanted us to learn Bangla well enough to dream in it. And yet, when I showed up to school, the administration assumed I didn’t know English. It took just a few days to realize I was just shy—a common trait among children of immigrants navigating new worlds for the first time.

Being bilingual has shaped everything about my career. Speaking Bangla allowed me to report deeply within Bangladeshi communities and, later, to work as a foreign correspondent in Bangladesh—fulfilling my dream of beocoming an international journalist. My fluency gave me access to stories that would have been impossible otherwise. I also picked up Hindi through Bollywood—another unexpected bridge between cultures.

Still, I live my own contradiction. I’m raising a five-year-old and a two-year-old, and I mostly speak to them in English. My mother scolds me for it, and she’s right. I’m proud of my language and preach the value of bilingualism everywhere I go. Yet I haven’t done enough to pass it on. Maybe it’s fatigue. Maybe it’s the comfort of expressing myself in the language I write and think in—English, the language that’s shaped my career.

I know I’ll come back to Bangla, to raise my kids bilingual. But for now, I’m allowing myself to rest from that constant tug-of-war over identity. It doesn’t have to be a crisis—if I choose to hold it differently. And watching Bad Bunny take the Super Bowl stage is a reminder not to lose the very thing I’ve been preaching about all along: the power of language, culture, and resisting the pressure to conform.