In Altadena, Black Homeownership Defied Segregation and Paved the Way for Future Generations

It was a symbol of freedom.

In the aftermath of the devastating Los Angeles wildfires, headlines about celebrities losing their mansions dominated the news. But there's a much bigger story that's not getting enough attention: among the thousands of homes burned down and dozens of lives lost were those of a historic multicultural community. Nestled in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, Altadena was one of the first places in the United States that let black families own homes.

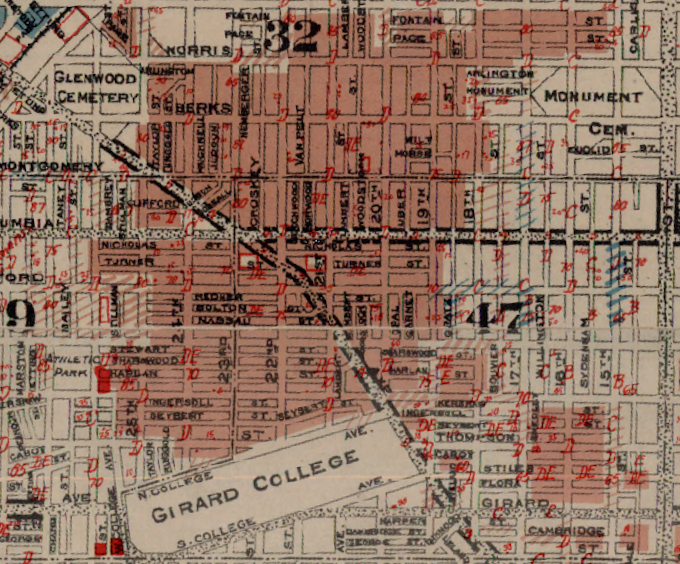

Here's why this matters: back in the 1930s, the government started a practice called redlining. They took maps and drew red lines around Black neighborhoods, marking them as "too risky" for home loans. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) followed suit, refusing mortgages in Black neighborhoods regardless of residents' financial stability. They even required builders to promise not to sell new homes to Black families.

But Altadena was different. While Pasadena played by the rules of segregation, Altadena became a refuge for black families and eventually other sidelined communities during the civil rights era. Some white homeowners and real estate agents quietly broke the rules and sold to Black families who had nowhere else to go. This spirit of defiance helped build a thriving Black middle class, including pioneers like science fiction author Octavia Butler and actor Sidney Poitier.

Other minority groups faced similar struggles when it came to homeownership and putting down roots throughout American history. Latino communities were forced into specific neighborhoods and cut off from opportunities like capital for starting businesses or buying homes. Asian immigrants, especially in the early 20th century, were labeled "undesirable" or "alien" by real estate developers and lenders. Long before redlining, federal policies like the Indian Removal Act and the Dawes Act had already disrupted Native lands and sovereignty. Redlining just made things worse, pushing Indigenous communities out of urban areas and away from opportunities, or even off their ancestral lands. Meanwhile, Jewish Americans, especially those from Eastern Europe, were also shut out of many suburban neighborhoods due to restrictive covenants.

Then, in 1968, the Fair Housing Act was passed, banning discrimination in housing based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It opened doors for marginalized communities to find homes all over the country. But in reality, it took a long time for discriminatory practices to die down, and their effects still ripple through to this day. Altadena led the way to break these racist practices.

Today, 58% of Altadena's residents are people of color. That's what makes the L.A. wildfire losses cut so deep. Pieces of hard-won history are lost. Homes that represent generations of resistance against discrimination are lost. The wealth that these families built despite every system being rigged against them is lost. When these communities were banned from buying property almost everywhere else; when they finally found one place willing to give them a chance, that home became more than walls and a roof. It becomes proof that the American Dream isn't just for some people.

Now Altadena faces another fight: how to preserve and protect a legacy of hope that's worth more than any mansion.

In an interview with PBS, Victoria Knapp, chair of the Altadena Town Council said, “Someone is going to buy it and develop who knows what on it. And that is going to change the character of Altadena.”

Read more:

A forgotten history of how the U.S. government segregated America (NPR)