Ramadan on the Shelves, Resistance Under Siege: A Conversation with My Child

How do I explain to my preschooler that while Ramadan has gone mainstream, our right to speak out remains under threat?

"Why doesn't anyone have Ramadan decorations up?" My four-year-old daughter's question stopped me in my tracks as we walked to school in the morning just days after the holy month of Ramadan —when billions of Muslims all over the world fast from sunrise to sunset—began. At home, purple and gold-themed crescent moons and stars adorned our walls and tabletops. Twinkling lights and lanterns were strung up across our living room window curtains. My younger sister came over to help my daughter hang up a festive "Happy Ramadan" sign over the weekend, our newest tradition that started after she was born during the pandemic.

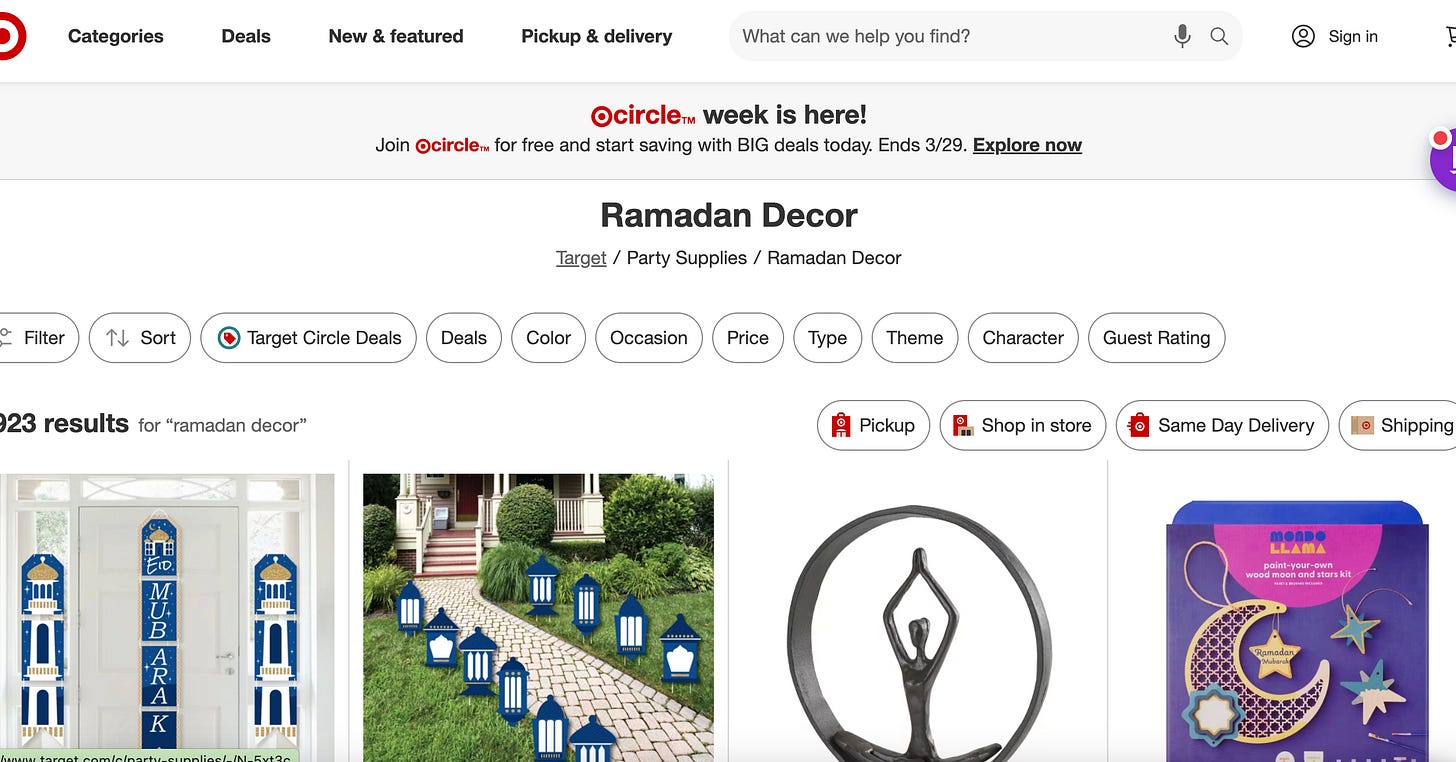

We're part of a growing trend—millennial Muslims have transformed Ramadan décor into a sophisticated market spanning high-end retailers, artisanal Etsy shops and Target. But what does this visibility mean when Muslims are still seen as inherently dangerous, anti-American, and face extreme levels of hate on a constant basis?

When I was my daughter's age, Ramadan was a quiet, almost private observance. There were no elaborate decorations or themed partyware. We celebrated with intimate family meals, and a new outfit for Eid—the holiday that comes after a month of fasting for Ramadan. Eid wasn't a recognized holiday, it was just a day I missed school. Today, my daughter attends my elementary school alma mater where Ramadan is acknowledged through arts and crafts and Eid is an official holiday in dozens of school districts across the country. Last year, I sent her to class with carefully curated Eid gift boxes for her classmates—small, joyful reminders that our traditions were worth celebrating and sharing. This year, we had the option of visiting a Ramadan street market, attending museum-hosted iftars—experiencing a version of Ramadan that is both deeply personal and publicly visible.

How do I explain to my daughter that while Ramadan decorations are sold at Target, the mere act of supporting certain political causes concerning Muslims can cost someone their job, their education, their life? Even as Ramadan-themed home collections likely turn a profit for big box retailers, Muslims and our allies speaking out against injustice are punished. Just a few weeks ago, Mahmoud Khalil, a recent Columbia graduate and permanent U.S. resident, was detained by the Department of Homeland Security while returning home after breaking fast with friends. By his side was his wife Noor Abdallah, who is eight months pregnant. The same schools that love to boast about inclusivity have no problem punishing Muslim students like Khalil for supporting Palestine and peacefully protesting.

Being politically Muslim at work also comes with immediate consequences. Last year, Hesen Jabr, a Palestinian-American nurse at NYU Langone, was fired for mentioning the genocide in Gaza. This was just one day after the hospital gave her an award for providing outstanding care to patients suffering perinatal loss. It isn’t just limited to professional life.

The most horrific example of the demonization of simply Being Muslim in Public was the death of six-year-old Palestinian-American Wadea Al-Fayoume in Chicago who was stabbed to death by his pro-Israeli landlord.

We are welcome as long as we remain apolitical, as long as our Islam is confined to decorations and dinner parties and fashion trends and the associated influencer content. But when a political event takes hold where Muslims are demonized once again or the moment we express solidarity with our fellow Muslims, with the diaspora we call the ummah—we are seen as anti-American and labeled terrorist sympathizers.

After 9/11, being Muslim became inherently political in America. Growing up in NYC as a teenager when the attacks happened, I had always identified more with my South Asian roots than my Muslim ones. But suddenly, I was unmistakably Muslim in everyone's eyes. My mother had recently started wearing hijab as she grew more connected to her faith, and for the first time, she was called a racial slur in our supposed sanctuary city.

For years, we were told that visibility was the goal. If people just saw us, understood us, they—the nebulous American or western collective—would welcome us into the cultural mainstream and Islamophobia would wither away. But here we are, in an era when Ramadan décor is marketed as a seasonal trend, and yet the simplest expression of Muslim political consciousness is often treated as subversive, dangerous, and un-American. Muslim presence is tolerated only as an aesthetic, never assertive in its accord with the ummah. Revelry, but not resistance.

The Council on American Islamic Relations recorded the highest number of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab complaints in 2024 since it began publishing data in 1996. As a journalist, I've witnessed firsthand how Muslims in America have faced deep suspicion despite making up just one percent of the US population. The government played a significant role in this vilification, which escalated dramatically after 9/11 when everyone became vulnerable to scrutiny.

As the Center for Constitutional Rights notes, the "war on terror" built upon existing hostility toward Palestinians, with post-9/11 surveillance programs expanding to target Arabs and Muslims broadly. Before 2001, the term "Muslim American" barely existed in public discourse—appearing only 437 times in news sources from 1986 to September 10, 2001. After 9/11, mentions exceeded 10,000. What was once barely discussed became central to national conversation, ultimately leading to policies like Trump's 2017 Muslim ban, which is rearing its ugly head again.

The front door my daughter pointed out on that morning walk had Halloween decorations up last fall, then Thanksgiving, and eventually Christmas. For Ramadan, it remained just a plain old door—no string lights, no twinkly lanterns, no moon and crescent decorations. Her question became the first lesson in explaining the multicultural, interreligious, multiracial country we live in where just one percent of the population is Muslim but our community is growing at a rapid rate.

My daughter is growing up in a time when Ramadan has, in some ways, never been more publicly acknowledged—major retailers now sold Ramadan décor, children's publishers released beautifully illustrated books about fasting, and city-sponsored street markets celebrated the month. Muslim moms like me are invited to read books about Ramadan and Eid to our kids' elementary school classrooms.

But, one day, my daughter will be old enough to understand the complexities of being Muslim in America. She will learn that visibility is not the same as belonging. That representation does not mean protection. That our traditions can be commodified while our voices are erased.

She will also learn that the fight for true belonging is not just about easily buying Ramadan decorations, but about ensuring that Muslims can express their full range of political and social concerns without fear—about refusing to let our celebrations become mere aesthetic distractions from the struggles we are still fighting. For now, though, she will know that her joy is valid.

Her traditions are worth celebrating.