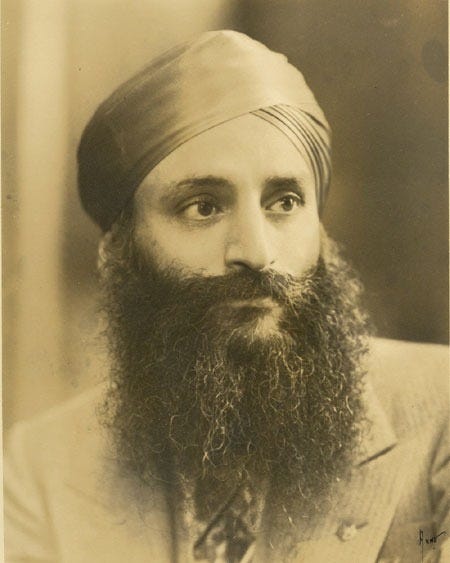

The Caucasian Who Wasn't "White Enough" to Become an American Citizen

How Bhagat Singh Thind's landmark fight for citizenship exposed America's shifting racial goalposts

It's 1923. Bhagat Singh Thind, a U.S. Army veteran who fought in World War I, stands before the Supreme Court. His case boils down to this: "You said only white people can become citizens. You also said 'white' means 'Caucasian.' Well, according to your own scientists, I'm Caucasian. So where's my citizenship?"

Just one year earlier, in Ozawa v. United States, the Supreme Court had ruled that only "white persons" or those of "African nativity" could naturalize—and that "white" specifically meant "Caucasian." The Supreme Court unanimously rejected Takao Ozawa's citizenship application, ruling that Japanese immigrants were not "white persons" eligible for naturalization, despite Ozawa's arguments about his light skin color and Western cultural assimilation. So Thind and his lawyers presented a seemingly airtight case: anthropologists classified Indians as "Caucasian" or "Aryan," therefore Thind qualified as "white" under naturalization law.

But here's where it gets ridiculous. The Court essentially said: "Well, yes, technically you might be Caucasian... but come on, we all know you're not really white."

In that moment, the mask slipped. Whiteness was never about science or biology—it was about keeping certain people in and others out. When Thind played by their rules and won, they simply changed the game.

Bringing the Revolution to America

Thind moved to the U.S. from India in 1913 at twenty-one years old. Like many Punjabi Sikhs at the time, he found work in the Pacific Northwest lumber mills. He was also involved with the Gadar Party, a revolutionary group based in San Francisco fighting to kick British colonizers out of India.

When World War I broke out, Thind actually joined the U.S. Army and was stationed at Camp Lewis in Washington. While serving, he applied for citizenship in 1918 and got it. But the government snatched it back just four days later, claiming he wasn't a "white man" and therefore ineligible.

Thind tried again the following year in Oregon and succeeded in 1920. But the Bureau of Naturalization couldn't let it go–they appealed, and the case wound up before the Supreme Court in early 1923.

What made Thind's case so fascinating was how South Asians occupied this weird limbo in America's racial imagination. Depending on who you asked and what day it was, they might be considered white, non-white, Asian, Black, not Black, or compared to groups like Jews, Armenians, and Latinos. Their racial classification seemed to shift like sand.

A Rigged System

The Thind case reveals a painful pattern that has shaped Asian American history: the pressure to align with whiteness—both legally and culturally—to survive in America.

For early South Asian immigrants—primarily Punjabi Sikh farmers and laborers who arrived on the West Coast in the early 1900s—this meant emphasizing their "Aryan" heritage and distance from Blackness. For Japanese immigrants like Takao Ozawa, whose citizenship case preceded Thind's, it meant highlighting their assimilation, Christianity, and Western values. All trying to distance themselves from being seen as foreign, different, or—let's be honest—associated with Blackness.

The message from America was clear: "Be as 'white' as possible in how you act, talk, and live—though we'll still never fully accept you."

When Thind's case failed, the consequences were brutal. Indians who had already become citizens had it stripped away. Some lost their farms and businesses because "aliens" couldn't own land. Families were torn apart. Men who had literally fought for America suddenly weren't American enough.

The Hierarchy of Belonging

This history established what Claire Jean Kim, Professor of Political Science and Asian American Studies at UC Irvine calls a "racial triangulation" of Asian Americans—positioned as perpetual foreigners, yet held up as "model minorities" in contrast to Black Americans. This triangulation serves white supremacy by:

Creating divisions between communities of color

Pressuring Asian immigrants to distance themselves from Blackness to gain provisional acceptance

Fostering the illusion that proper assimilation and hard work, not systemic change, was the path to acceptance

The anti-Black implications were not accidental. As Asian immigrants struggled for a foothold in America, many were encouraged to see alignment with whiteness—not coalition with other marginalized groups—as their salvation.

Fighting Back

Despite having the deck stacked against them, South Asian immigrants built resilient communities. They formed advocacy organizations such as the India America League of America which fought for citizenship rights in 1938. When banks wouldn’t serve them, they created informal banking systems called "kameti" or "chit funds" where community members pooled money.

And not everyone played along with the racial hiearchy, Some Indians formed professional and personal partnerships with Mexican Americans and Mexican-Hindus" or "Punjabi-Mexicans" emerged as a distinct community in California agriculture. South Asian and Black alliances formed in the civil rights era.

Where We Stand Today

The 1965 Immigration Act eventually reopened doors, bringing waves of professionals from South Asia and later their families. Today's South Asian American community is vibrant and diverse—from tech execs to taxi drivers, doctors to small business owners.

But Thind's story still matters. When I look at how South Asian Americans sometimes still chase proximity to whiteness—through professional success, cultural assimilation, or political alignment (a few of these wonderful folks are hanging out with Trump these days)—I see echoes of that old pressure.

The real question for us today is: Are we reinforcing the same hierarchies that hurt our ancestors? Or are we working to tear down a system that made us chase an acceptance that kept moving beyond reach?

Here's what I think: The lesson of Bhagat Singh Thind isn't just about a legal defeat. It's about recognizing how systems of power will change their own rules rather than share that power. And it's about choosing whether we'll continue playing a rigged game or work together to create new rules altogether.

Drop me a note if you have thoughts on today's story!

LEARN MORE:

The Whiteness Myth (NPR)

The Problem (South Asian American Digital Archive)