What Country Are My Children Inheriting

A new Supreme Court ruling chips away at birthright citizenship. For families like mine, the promise of America has never felt more fragile—or more worth fighting for.

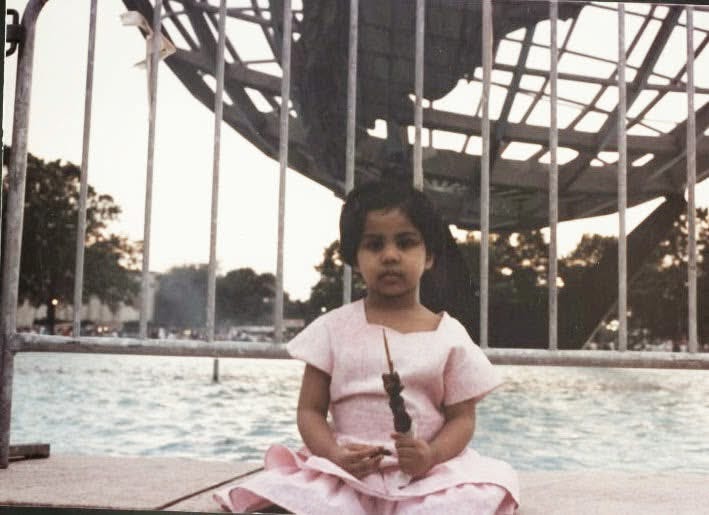

The slurs thrown at me in 1990s New York weren't about being Muslim. Greek, Colombian, and Puerto Rican kids called me "bindi" and "Hindu"—generic insults for anyone who looked South Asian. The irony was lost on them: they thought "Indian" and "Hindu" were damning enough without bothering to learn the difference. My actual faith didn't matter on the street. What mattered was my skin.

That changed after September 11, 2001.

I was seventeen when the towers fell, and suddenly my spiritual identity became a political liability. My mother had started wearing hijab just a year earlier, making our family newly visible in ways we were still learning to navigate. But after 9/11, visibility became danger. We weren’t just immigrants anymore—we were suspects in our own country.

The mysticism and poetry of Islam that had always lived quietly in me suddenly had to stand trial in the court of public opinion. I’ve never been the “perfect” Muslim girl, but my Sufi spirit—that inward-looking faith that teaches love as resistance—was something I couldn’t abandon, even when the world demanded I defend it.

Twenty-four years later, I find myself asking: What country are my children inheriting?

Because this summer, the Supreme Court brought us closer than we’ve been in over a century to answering a fundamental question: Who gets to be American?

On June 27, 2025—just days before Independence Day—the Supreme Court issued a divided ruling that, while not directly overturning birthright citizenship, severely limited federal judges’ power to block President Trump’s executive order restricting it. The order directs federal agencies to deny automatic citizenship to children born in the U.S. to undocumented and temporary visa-holder parents.

Three lower court judges had initially ruled the order likely violates the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause. But with the Supreme Court now curbing nationwide injunctions, the administration is free to enforce it while legal challenges slowly wind their way through the courts.

The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, was designed to protect the citizenship of formerly enslaved people. It declares that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.” That promise was reaffirmed in 1898 in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, when the Court ruled that a man born in San Francisco to Chinese parents—non-citizens barred from naturalizing—was nevertheless an American citizen.

That precedent has held for over a century. Now it faces its gravest test.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, around 4.4 million U.S.-born children live in mixed-status households with at least one undocumented parent. These aren’t legal abstractions. They’re kids in our classrooms, on our playgrounds—children whose futures hinge on whether this country sees them as fully American.

For immigrant communities—especially Muslim, South Asian, and undocumented families—this isn’t new terrain. We’ve lived under suspicion and surveillance before. But this moment feels heavier. This time, citizenship itself is on the line.

Following the October 7 attacks and the war in Gaza, anti-Muslim hate surged dramatically. According to Stop AAPI Hate and the Council on American-Islamic Relations, 2024 saw one of the sharpest spikes in anti-Muslim incidents since 9/11—from school bullying to workplace firings to physical assaults. Meanwhile, the Department of Justice has prioritized the process of denaturalization, a legal process that strips naturalized Americans of their citizenship—once a rare tool, now a political weapon.

In this climate, birthright citizenship becomes more than a legal principle. It becomes a test of whether the United States will remain a nation of laws—or evolve into one of inherited exclusion.

Yet even in this dark constitutional moment, there are flickers of light.

Zohran Mamdani, a 33-year-old Muslim of South Asian descent from Uganda, defeated former Governor Andrew Cuomo in the Democratic mayoral primary in New York City. Born in Kampala, Zohran moved to New York as a child and became a U.S. citizen only in 2018.

His victory is more than political. It’s symbolic. In a city that once surveilled Muslim communities through secret NYPD programs, a Muslim man—whose citizenship was earned, not inherited—is now poised to lead.

This is the paradox of our moment. While the federal government narrows the definition of who belongs, New Yorkers have chosen someone whose very identity defies every exclusionary instinct baked into our history. Someone whose story speaks to the vast, complex, border-crossing reality of American life.

The fight over birthright citizenship is ultimately a fight over whose children get to claim this country as their own. It’s a legal battle, yes—but also a moral and generational one. Will we be a nation that upholds its promises? Or one that moves the goalposts when those promises include people we’ve long considered outsiders?

The 14th Amendment was born from our country’s deepest reckoning. What we do now will decide whether its promise still holds. Whether “citizen” is a birthright—or a privilege subject to revocation.

What does birthright citizenship mean to you? How are you processing this moment?

Reply to this email or share your thoughts using #PortOfEntryNewsletter and tag me on Instagram!

I was a beneficiary of birthright citizenship, though I didn’t know it until many years later. I knew this administration wouldn’t stop with birthright citizenship. The denaturalization mandate is especially worrying, as it would effectively enforce second-class citizenship. Thank you for shining a light on these developments, however troubling, and for sharing pieces of your life. I always appreciate your perspective, Jennifer.