What does it mean to be a Middle Eastern and North African New Yorker?

A new exhibit at the New York Public Library showcases stories of New Yorkers from the MENA region

In 1910, Muhammad Judah sailed from Algeria to New York, carrying whatever hopes bring a person that far from home. At Ellis Island, he faced the question that ended his journey: “Do you practice polygamy?” Under the Immigration Act of 1891, polygamists were barred from entry. He never set foot in the U.S.

I came across his story at the New York Public Library’s (NYPL) Niyū Yūrk exhibition, open through March 8, which traces 140 years of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) lives in New York.

“When I joined NYPL three years ago, I realized that we had long been collecting materials produced by these communities as well as materials gathered to serve them dating back to the late 19th century,” explained Hiba Abid, the very first curator of Middle Eastern and Islamic studies at NYPL. “This exhibition became an opportunity to give MENA history a visible voice and presence in New York.”

This effort to centralize and showcase MENA histories also illuminates how these communities navigated the racial hierarchies of their time. Early immigrants quickly learned that race was the master category of belonging in America, shaping who could claim citizenship, own property, or gain social legitimacy.

What It Means to Be “White”

Christian Syrian and Lebanese communities who are among the first immigrants from the MENA region litigated their way into whiteness by showing their ties to the Holy Land at the turn of the twentieth century, when citizenship was limited to free white people and the formerly enslaved.

This is part of the reason why the the U.S. still classifies MENA people as white—a legal designation rarely reflecting lived experience. New York State is finally breaking with that history: state law now requires agencies to track Middle Eastern and North African communities separately from the “White” category, listing Egyptians, Moroccans, Algerians, Palestinians, Iranians, and more.

NYPL’s exhibition offers a window into that complicated history.

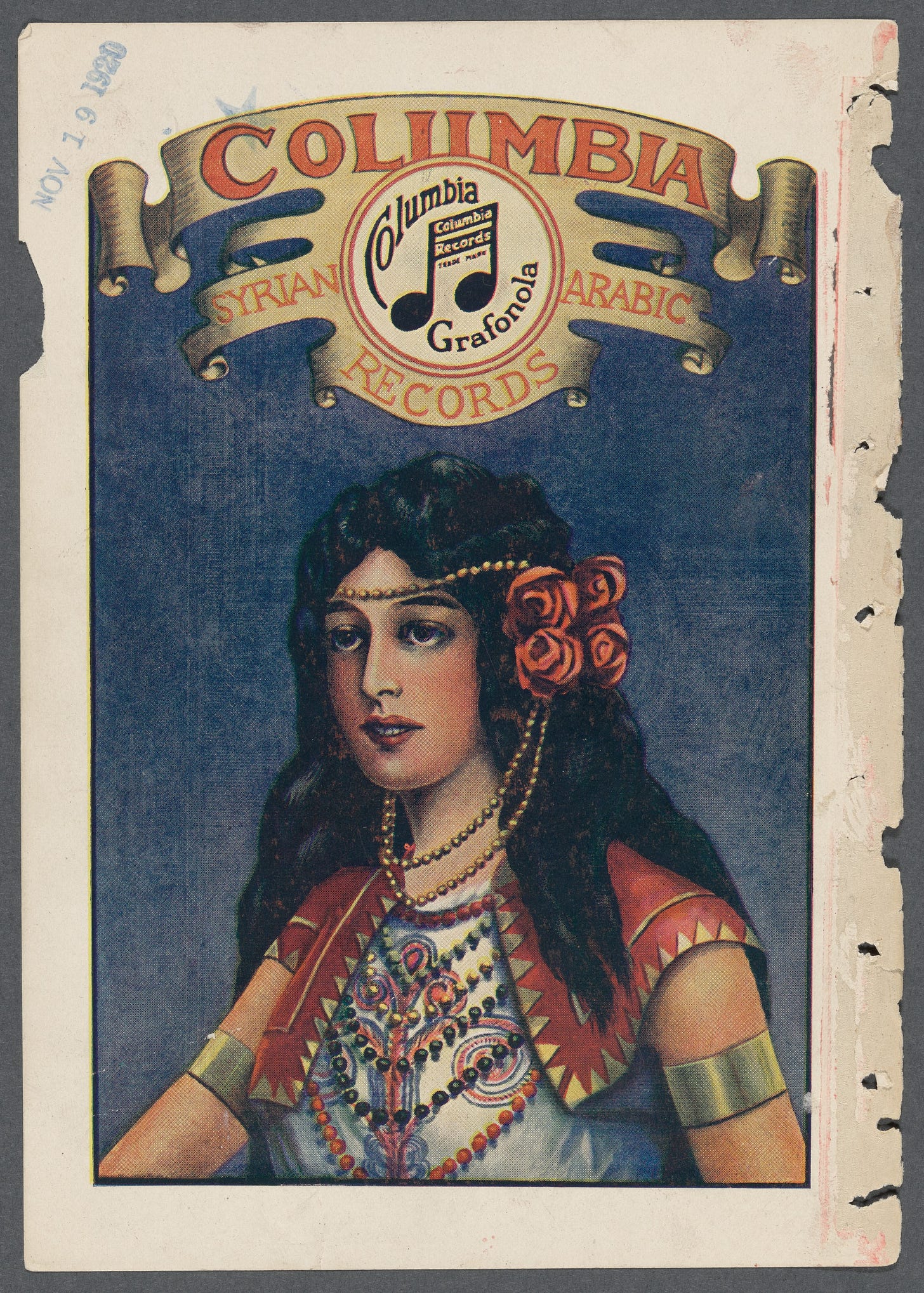

The exhibition shows how MENA communities documented themselves when official histories ignored or misrepresented them. The New York Public Library collected newspapers in Arabic and Armenian starting in the 1890s, some of them existing nowhere else in the world. Business directories from 1908 listing every Arab business in New York. Middle Eastern records by major American music company Columbia and Victor in the 1930s because they realized this growing community was craving music from back home.

The Pen League, including Kahlil Gibran, reshaped Arabic literature, tackling immigrant life and serialized in newspapers because American publishers would not. They self-published and built their own platforms—an act of survival and freedom.

Performing Belonging

There’s a section of the exhibition on self-orientalization that I can’t stop thinking about. Hassan Ben Ali, a Moroccan acrobat, literally brought camels to Coney Island in the early 1900s. This was peak American orientalism in popular culture—a legacy of World’s Fairs where performers learned that Americans wanted exoticism, the “East” they’d invented. So early immigrants gave audiences what they expected.

But as the community grew, so did resistance to tropes. In the 80s and 90s, the Iranian playwright Reza Abdoh staged productions in hotel receptions, ballrooms, parking lots, streets—avant-garde theater that put him at the forefront of New York’s experimental scene.

Mutual Aid and Survival Across Generations

The exhibition also traces something quieter—mutual aid.

Early MENA communities built networks of survival. In 1907, the Syrian Ladies Aid Society—Lebanese, Palestinian, and Syrian women—taught English, helped newcomers find housing, and supported small businesses. Today, Egyptian-American organizer Rana Abdelhamid carries on that legacy in Queens, fighting gentrification, building political power, and advocating for census recognition.

Documenting while fighting back

What the exhibition also reveals is the absence of post 9/11 storytelling.

“These communities were busy fighting back, hiding, surviving. Libraries were probably the last thing on their minds and not institutions they saw as repositories for their archives or organizing efforts,” explained Abid. “That’s something I’m deeply concerned about today. We need to ensure that this history is preserved through materials produced by the community itself, not filtered or narrated by others.”

In the 2001 documentary The Complexity of Living as an Arab in America, filmed just weeks after 9/11, a Palestinian American woman says it plainly: as long as she is Palestinian and American, she will never be safe. Being both means being neither.

Muhammad Judah’s story ends at Ellis Island but his experience is transformed and continues in every citizenship guidebook still being passed around, in every mutual aid network, in every bodega owner, every self-published zine, every artist refusing to explain themselves and every organizer fighting gentrification and census misclassification.

Thank you. I’ll be sure to see it now, because of your post!