What Happens to Children Taken by ICE?

Inside detention centers and federal buildings like Manhattan’s 26 Federal Plaza, children are separated from their parents, held in undisclosed locations, and left with emotional and physical wounds.

The last place a child should disappear is inside a federal building. On the morning of November 26, six-year-old Yuanxin and his father, Fei, entered 26 Federal Plaza in Manhattan for a routine check-in with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Fei was then transferred to Orange County Jail, more than an hour away, and Yuanxin was gone.

Volunteers who accompany families to ICE appointments say this is not an isolated incident. “They just don’t come out,” one said. “Entire families have gone in and not come out.” Days later, Representative Nydia Velázquez’s office confirmed that Yuanxin had been transferred to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), though officials would not disclose the exact location. A six-year-old boy, newly enrolled in first grade at P.S. 166Q in Astoria, Queens, was now separated from his father.

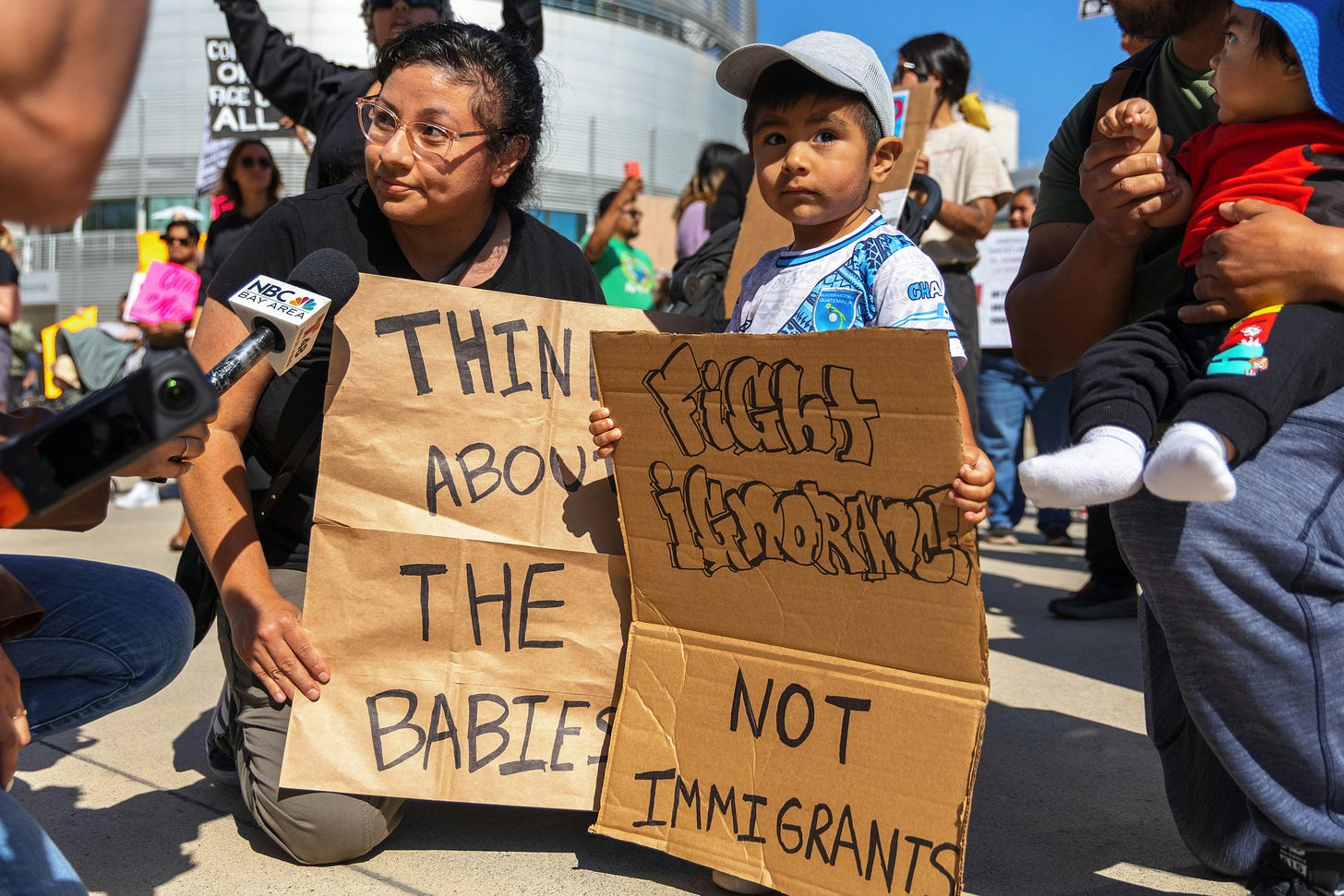

“We understand that Yuanxin is safe, but he is being held somewhere where nobody who knows him or cares about him can see him or give him a hug and make him feel safe,” Devora Fein, a leader of the western Queens chapter of Indivisible, the group that organized a rally in Astoria in support of Yuanxin, told the crowd. “He is not the only one.”

Federal data obtained by the Deportation Data Project at UC Berkeley shows that more than 2,600 immigrant children across the country have been arrested this year.

According to experts, when kids are separated from their parents during immigration enforcement, the psychological fallout is immediate and measurable. Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, are traumatic events that occur in childhood and are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance abuse in adulthood, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The toxic stress from these experiences can change brain development and affect how a person’s body responds to stress.

Advocates and activists consistently argue immigration enforcement isn’t just a legal process—it’s also a public-health crisis for children. A study published in the European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry journal in August examined 425 children in detention and found that those who had been taken from their mothers showed almost double the rate of emotional problems compared to kids who weren’t separated. Nearly half of the separated kids struggled emotionally, and about a third of all detained children showed serious signs of distress—things like withdrawal, anxiety, emotional volatility. Researchers point out that this isn’t just the stress of migration itself. The trauma of detention, separation, and uncertainty piles on top of whatever a child has already lived through—making everything worse.

“When your childhood memories are rooted in fear—worrying if your parents will be there at the end of the day—it flips everything upside down. Kids are supposed to be wrapped up in their own little worlds, their own big feelings. But when you’re the one watching the door, listening for sounds, trying to keep everyone safe, you grow up in ways you shouldn’t have to,” says Leisy Abrego, a sociologist and professor of Chicana/o and Central American Studies at UCLA who studies the impact of immigration policies on the well-being of immigrant families.

Fei and Yuanxin’s story illustrates this reality in real time. The family had already endured multiple detentions since arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border in April, seeking asylum. Twice, they were held in Texas family detention centers. They were released and granted parole for a year.

Experts tell me that kids growing up under immigration enforcement don’t usually say, “I’m anxious because ICE might come.” Instead, it shows up in quieter ways: trouble sleeping, suddenly withdrawing from friends, snapping more easily, or acting out in school. These aren’t random behaviors—they’re what chronic fear looks like in a child.

“If a family is living with the constant possibility of detention, a child can never feel fully secure,” said Dr. Sandra Espinoza, a family therapist in Los Angeles who works closely with immigrant families.

And it doesn’t stop at anxiety. Stress like this seeps into the body. According to the study, half of the detained children reported physical symptoms—mostly headaches and stomach pain. Malnutrition, dental issues and vitamin D deficiencies are also serious concerns for children held in detention centers. Chronic fear and instability have measurable consequences: they weaken immune systems, alter brain development, derail emotional regulation, and ultimately undermine the building blocks of a healthy childhood.

Detention length matters, too. A 2022 study of Central American and Mexican children who spent an average of just seven days in detention found much lower rates of PTSD—around 6.5%—compared with the 17% seen in long-term detention. Yuanxin has been separated from his father for several weeks already.

Yuanxin’s teacher described the 6-year-old as a bright, creative child who loves making puppets and playing with them. “He is incredibly good at math for a first grader, with amazing handwriting in both English and Mandarin,” she said. “Our class feels his absence every single day.”

Activists say his separation from his father is especially traumatic, given his young age and the fact that Mandarin is his primary language, which limits his ability to communicate his needs and emotions.

Studies show that 90% of detained children undergo body searches. Nearly three-quarters are taken without warning. Almost half are reduced to being identified by numbers instead of names—something that may seem small but, for a child, strikes at their sense of identity and dignity.

Fei and Yuanxin’s story reminds us that the real cost of enforcement isn’t just detention. It’s the way a six-year-old becomes a little smaller in the world—shouldering a fear he never chose, shaped by a system that was never built with his well-being in mind.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship Fund for Reporting on Child Well-being.

This is heartbreaking and necessary journalism. The human cost of these policies is carried by children who never chose any of this.

The part about kids being identified by numbers instead of names really landed for me. I remember working with refugee families and seeing how dehumanization compounds trauma in ways that aren't always obvious at first. What's especially troubling here is the double bind for young bilingual kids like Yuanxin beacuse the language barrier doesn't just limit communication but it actively isolates them from any support that might soften the separation. The 90% body search statistic is staggering when we consider its basically teaching children thatsurvival means accepting violation as routine.