DIASPORA DIALOGUE: LEGACY THROUGH BANGLADESHI FOOD

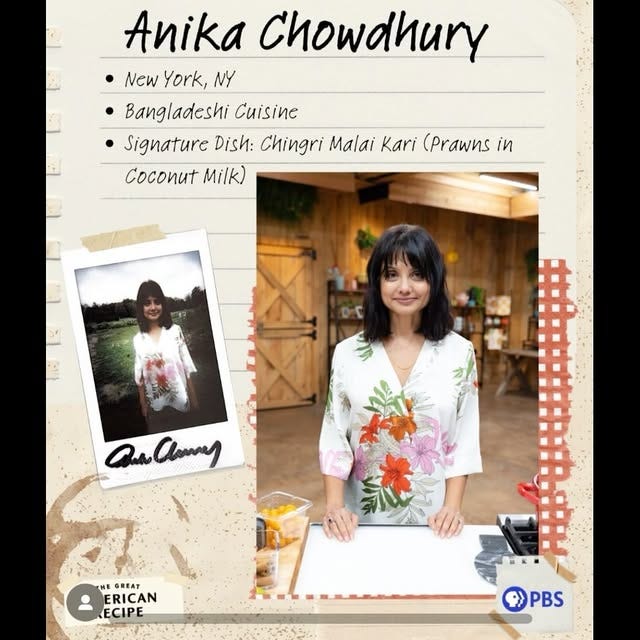

How Anika Chowdhury Turned Grief, Memory, and Family Recipes into a Celebration of Culture—Now Seen on PBS

One of the disorienting truths of diaspora life is how easily histories are lost—through war, migration, colonization, or silence at home. Many of us grow up knowing little about where we come from, or about other immigrant communities navigating similar paths. Diaspora Dialogues is a small course correction—a space where we sit down with the thinkers, creators, and cultural workers who help us understand what diaspora life really looks like. Whether they’re writing books, preserving histories, building businesses, or creating community spaces, these are the people exploring what it means to build a life, hold onto memory, and find belonging when home spans borders and generations.

When Bangladeshi American home cook and blogger Anika Chowdhury launched Kitchen Gatherings, it wasn’t for clicks or clout. It was an act of preservation. In the wake of losing both of her parents, Anika turned to the kitchen—not only as a space of mourning, but as a way to carry forward the legacy of generosity, storytelling, and deep-rooted cultural memory they left behind. Dishes that once filled a Dhaka kitchen with warmth during monsoon season became a way to reconnect with history, navigate the ruptures of diaspora life, and document a culinary tradition too often left out of the mainstream conversation. Now featured on The Great American Recipe(streaming on PBS), Anika is bringing Bangladeshi flavors—and the stories behind them—to a wider audience, one recipe at a time.

Subscribe for free to get new issues straight to your inbox—or become a paid subscriber to help sustain independent storytelling from the margins

How did your blog, Kitchen Gatherings, get started?

Anika. I was very close to my parents—my entire family, really. I’m the eldest of three; my sister is a primatologist, and my brother works for the United Nations and has lived in Switzerland for much of his career. We’re close, but not always physically together.

At the time my mom was diagnosed with cancer, my sister was living in Cape Town in South Africa. She moved back immediately. We were all very involved in caregiving—taking turns cooking, supporting each other, going to chemo. I had left my job to be there full-time. We were hopeful, but she passed away. And a year later, my dad was diagnosed with cancer. He passed two years after her.

That’s heartbreaking. I’m so sorry.

Anika: Thank you. It was a double blow. I was devastated and very depressed. My husband and I don’t have children, so I kept thinking, Who do I pass on their legacy to? That was the hardest part—grieving while holding the weight of that loss.

And so the blog was born from that space. My parents lived with so much generosity, a very Bangali kind of hospitality. If you grew up in Bangladesh—or even just visited—you know this: people will share what little they have. Even if it’s just dal-bhaat (lentils and rice), they’ll invite you in.

That spirit—that’s what my parents lived by. I thought: I want to share that. And food was the way to do it. They were amazing cooks. I still have recipe books handwritten by my nani and my mom. My dad once went to Bangladesh while my mom was in treatment, and the only thing I asked him to bring back were those recipe books.

Those family recipes of my grandmother’s and my mom’s (that included dishes that people don’t even make any more) were more precious to me than any material inheritance. So I started a blog—not just to archive recipes, but to tell the stories around them. The blog became a place to honor my parents, to talk about Bangladesh, our culture, our food traditions. I didn’t expect anyone to find it. It wasn’t even under my name—just Kitchen Gatherings. I only added my name just before the announcement of the PBS show.

Wait—PBS just found you?

Anika: Yes! One day, I got an email from someone at PBS. Honestly, I thought it was a scam. I didn’t even have my email address listed publicly. But my sister and husband said, “At least reply and find out.” I did some Googling, realized the name checked out, and finally responded.

Turns out they had read everything on the blog. They told me they loved my writing, the stories, the way I honored my family and culture through food. It was surreal.

That’s incredible. And so well-deserved.

Anika: Thank you. What’s wild is that they found me through Instagram—probably through a hashtag like #homecooking or something. I’m not a content creator in the traditional sense. I post when I feel moved to share something. I put a lot of care into making sure the recipes are replicable. Bangladeshi food is all about technique, and I want people to taste it the way it’s meant to be tasted.

I’m so glad they found you. Bangladeshi food is so underrepresented. Even in New York or London, where most “Indian” restaurants are actually run by Bangladeshis—you don’t see Bangladeshi food on the menu.

Anika: Exactly. I’ve asked so many restaurant owners over the years, “Why not include even one Bangladeshi dish?” And they always say, “If we put Bangladeshi on the sign, no one will come.” That’s the mindset. So I hope things like this— seeing Bangladeshi food on PBS—will help change that. Maybe more Bangladeshis will feel encouraged to proudly name and serve our food.

How do you explain Bangladeshi food to someone who’s never had it?

Anika: I usually say: it shares a spice palette with North Indian cuisine, but the dishes are quite different. What people know of Indian food is often restaurant food—rich, thick sauces. Bangladeshi dishes tend to have lighter gravies. There’s also a huge emphasis on vegetables. We have so many varieties of greens—shak—which are cooked in ways that preserve their texture and flavor. Think of spinach: in sag paneer, it becomes a paste. But in our cooking, you can still see and taste the leaves of the spinach.

And of course, we’re a country of rivers. Fish is huge. We have an enormous range of fish dishes, though it’s harder to find those fish here. Regionally, there’s so much variation too—like Sylhet which has its own identity and even its own dialect, and the food is tangy and totally distinct. I don’t think most people—even many Bangladeshis—realize how diverse our food culture is.

I was actually browsing your blog while we were chatting and saw the paturi recipe—chicken parcels wrapped in bottle gourd leaves. I laughed thinking: 12-year-old me would’ve refused to eat that.

The paturi recipe is stunning—not just the food, but the way you laid it out, the storytelling. I could see that dish in a restaurant.

Anika: That’s from my mom’s side. We’d always make it during the monsoon, when the gourd leaves were in season. It was a family event—everyone helping prep the immensely bony hilsa fish that the leaves would be wrapped around . I didn’t cook as a child, but I participated in the steps. Even making chapatis for my dad, who ate them every night. Preparing food was often a collective activity, and of course no one ate food alone by themselves – we always ate together.

Your cooking clearly reflects a wide range of influences. Can you talk about that history?

Anika: My mom’s side came from an old zamindari family, and both sides of her family married widely—even across borders. Some of the women came from North India, like the Muslim Surat region, so there’s a mix of Bengali,,, and more farflung culinary influences. Her dad’s side lost property during Partition; some of it was on the Indian side of the border in Malda. So I grew up with this expansive idea of what “Bengali food” could be—yogurt-based sauces, Mughal milk dishes, and lots of coconut milk from the southeastern side

.That makes so much sense. It reminds me of how strategic Bengal was historically—there’s that stat floating around that Bengal once held 12% of the world’s GDP.

Anika: Exactly. Bengal was central to British colonial revenue and global trade. That’s why our food is so diverse. The Portuguese, for example, left a major imprint. There are Bangla words like chabi (key), which mirrors the Portuguese chave, and janala (window), similar to janela.

That’s incredible. It reminds me of when I walked into a random Burmese restaurant in San Francisco and had the best chicken curry. I remember thinking, “Why does this taste so familiar?” It turns out, of course, there’s deep historical connection between Chittagong and Myanmar.

Anika: One of my grandmother’s specialties was a Burmese dish. She’d throw khao soi parties—noodle dishes that tasted both foreign and familiar. It all connects back to that fluid border culture.

It’s wild how connected everything is. One challenge with Bangladeshi food is that it’s hearty and homestyle, so it doesn’t always “plate pretty.” But you’ve cracked that.

Anika: Bangladeshi food isn’t always visually striking—it can be brown, blended, textured. But I want young diaspora kids or non-Bengalis to look at my photos and feel curious, even hungry. That’s how we keep the food—and the stories—alive.

If someone unfamiliar with Bangladeshi food came over, what three dishes would you serve to introduce them to our cuisine?

Definitely Bangladeshi chicken roast—familiar, comforting, but still distinct from Indian-style roast. If they like seafood, chingri malai curry—shrimp in coconut milk, rich and aromatic. And for a side, misti kumra with shrimp—sauteed pumpkin, sweet and savory.

But if I could sneak in a fourth, I’d serve biron polao—a Sylheti sticky rice dish we used to have at family brunches in Dhaka that my Dadi used to make, with potatoes and a rich egg curry on the side. It’s not well-known, even among many Bangladeshis, but it tastes like home to me.

That’s the beauty of your work—you’re documenting not just recipes but regional, personal histories that would otherwise get lost.

Anika: That’s exactly why I do it. Food is memory. And when we lose our elders, we risk losing those memories too. So I write, I cook, and I share. Because even if the audience doesn’t know what paturi or pishpash is, maybe they’ll taste the love behind it—and start asking questions.

"Food is memory." Love that! I hadn't heard of Anika before so thank you for shining a spotlight on her and on Bangladeshi food.

How did you find out about her?

Agreed - Bangladeshi food is underrated but it’s making waves in the culinary community. I wrote about a Bangladeshi chef who was nominated for a James Beard, if you’d like to check it out! https://centraldesi.beehiiv.com/p/meet-njs-first-desi-chef-nominated-james-beard